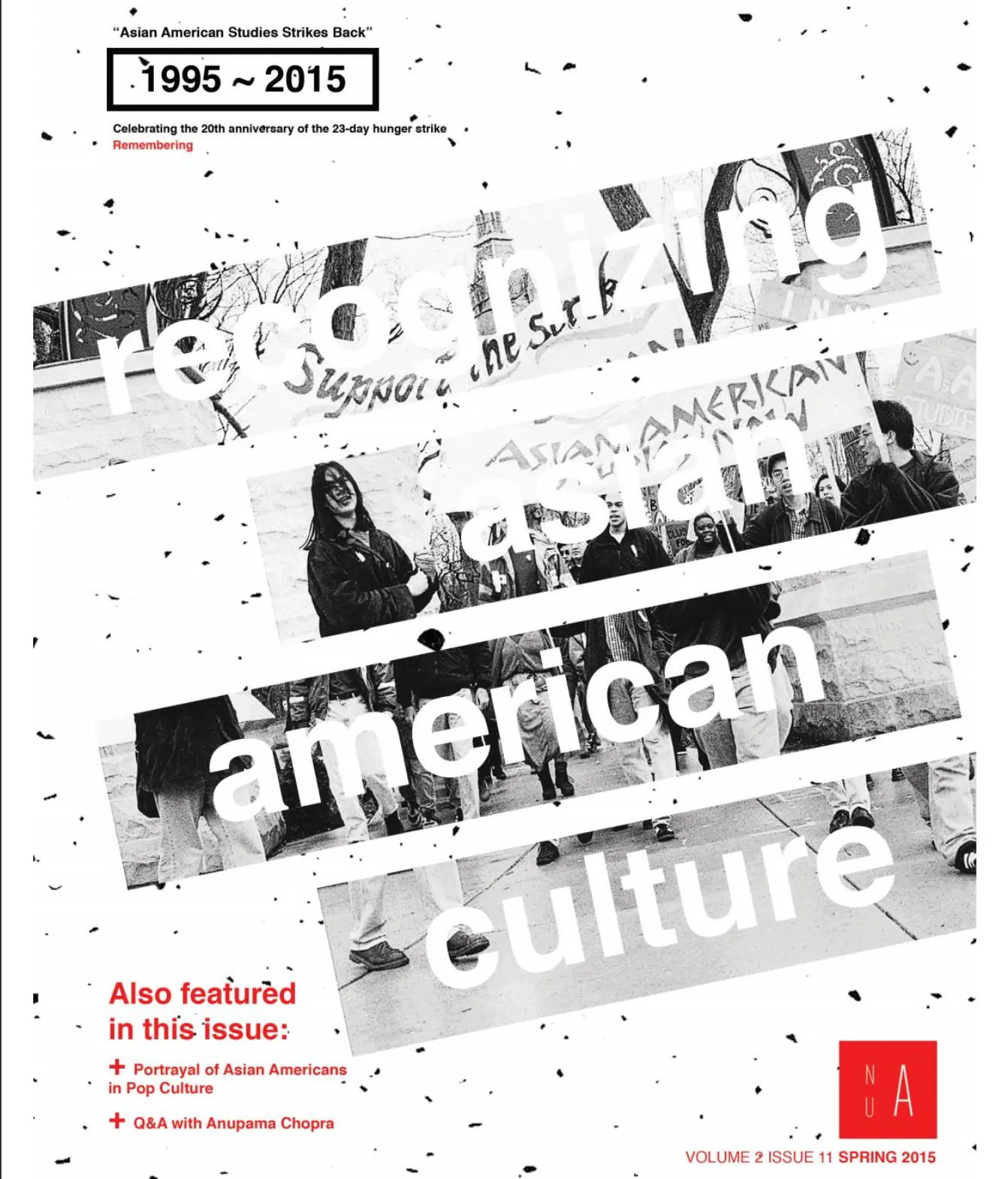

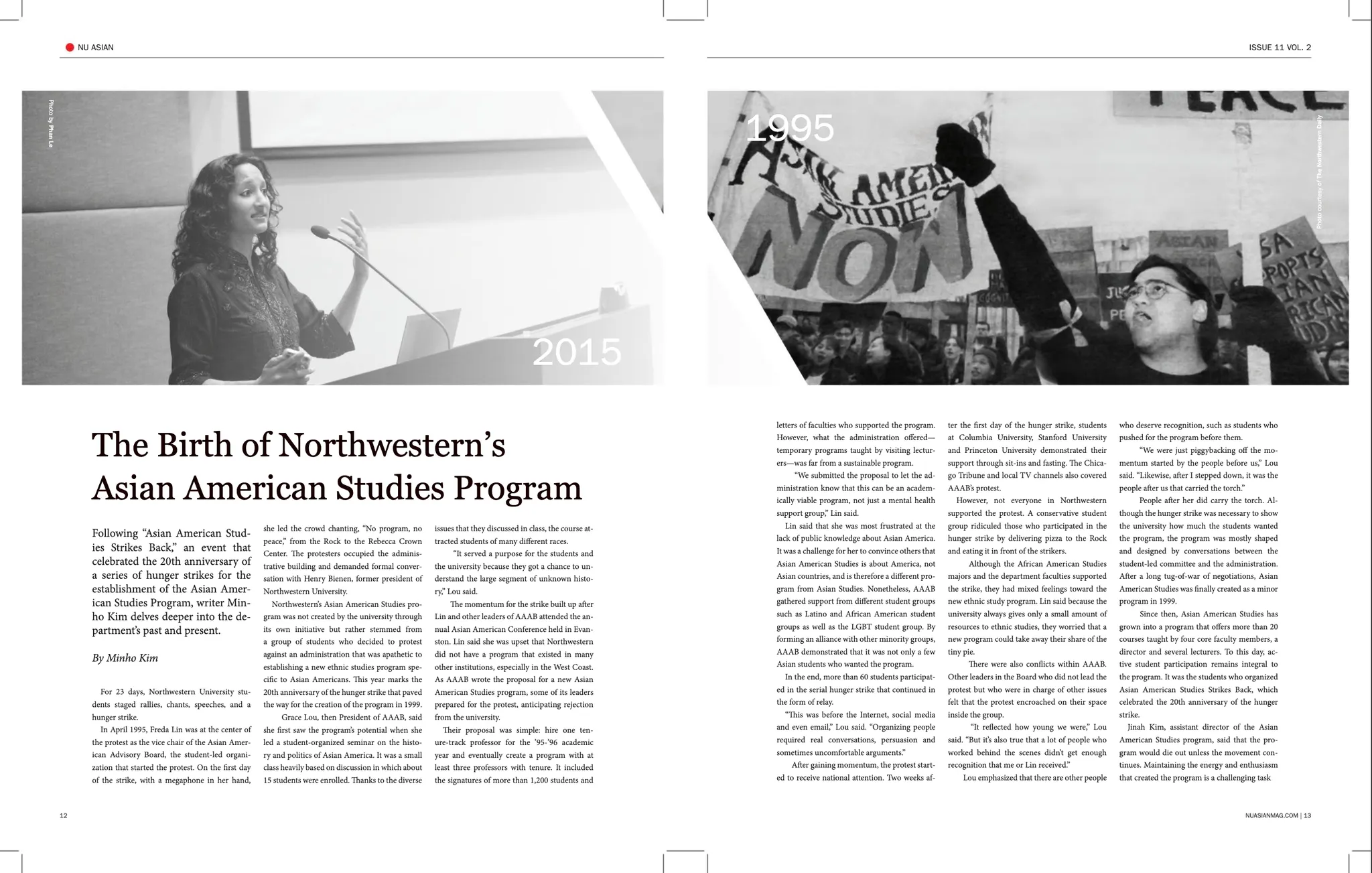

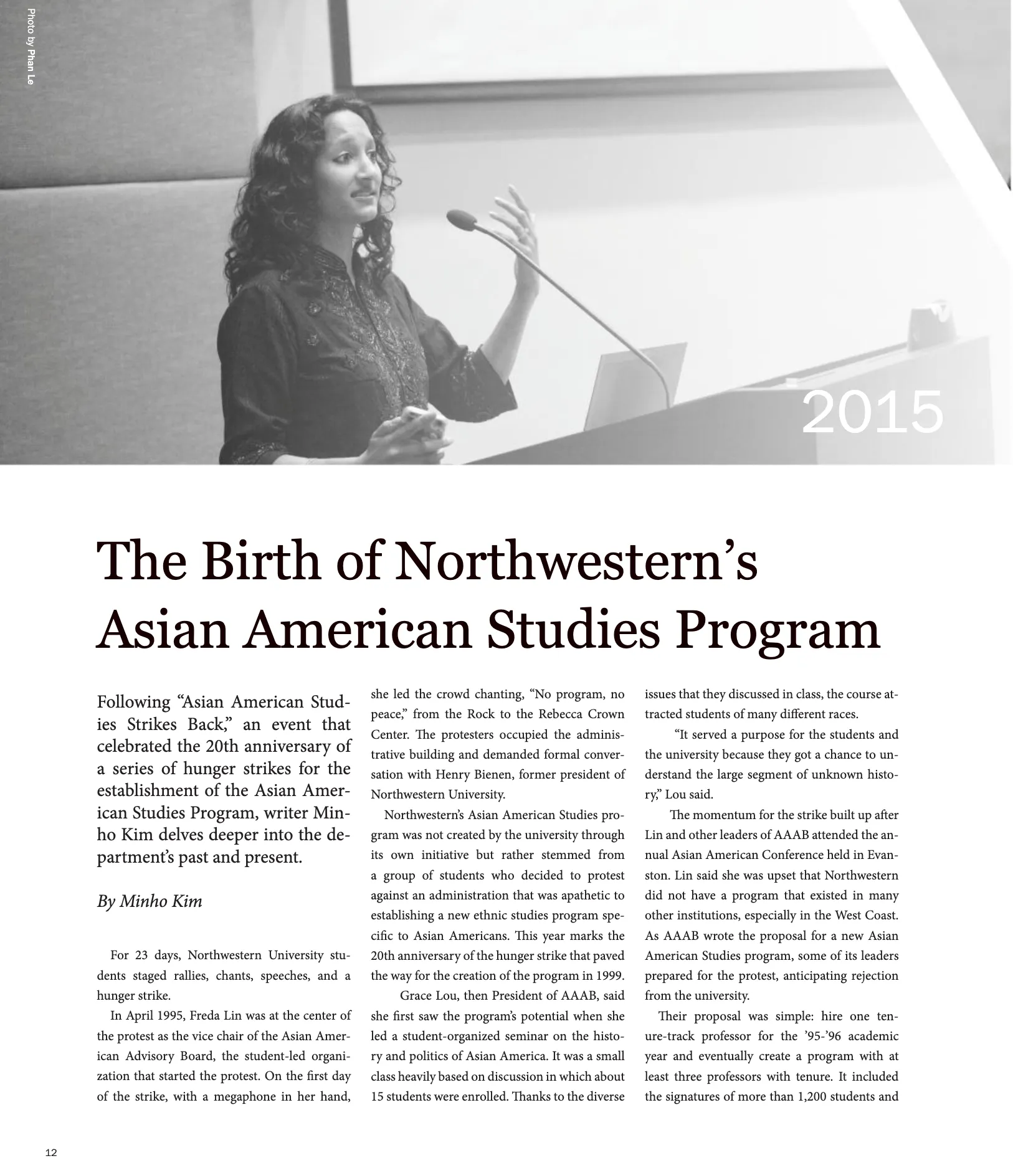

The Birth of Northwestern’s Asian American Studies Program

Following “Asian American Studies Strikes Back,” an event that celebrated the 20th anniversary of a series of hunger strikes for the establishment of the Asian American Studies Program, Minho Kim delves deeper into the department’s past and present.

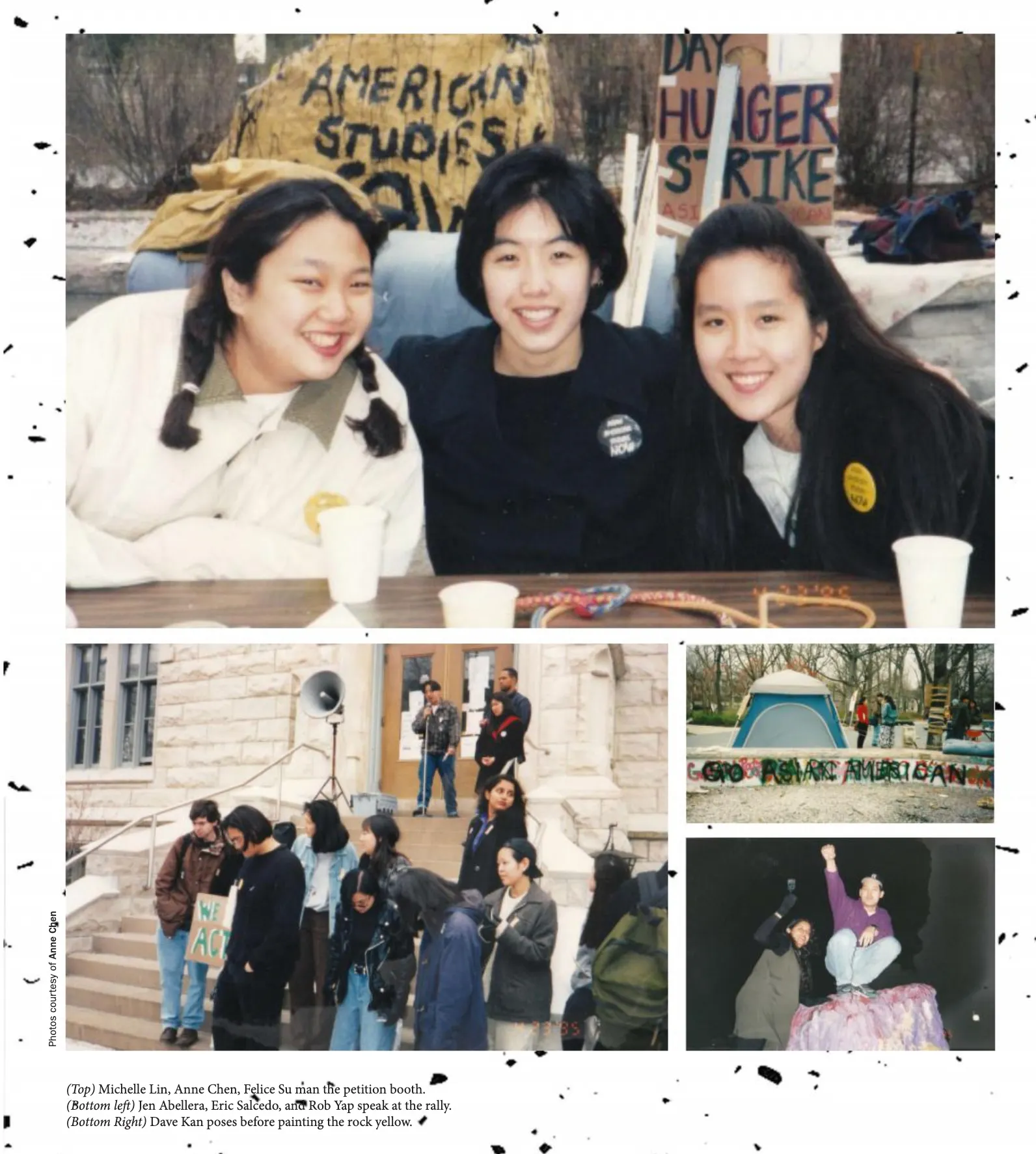

For 23 days, Northwestern University students staged rallies, chants, speeches, and a hunger strike.

In April 1995, Freda Lin was at the center of the protest as the vice chair of the Asian American Advisory Board, the student-led organization that started the protest. On the first day of the strike, with a megaphone in her hand, she led the crowd chanting, “No program, no peace,” from the Rock to the Rebecca Crown Center. The protesters occupied the administrative building and demanded formal conversation with Henry Bienen, former president of Northwestern University.

Northwestern’s Asian American Studies program was not created by the university through its own initiative but rather stemmed from a group of students who decided to protest against an administration that was apathetic to establishing a new ethnic studies program specific to Asian Americans. This year marks the 20th anniversary of the hunger strike that paved the way for the creation of the program in 1999.

Grace Lou, then President of AAAB, said she first saw the potential of the program when she led a student-organized seminar on the history and politics of Asian America. It was a small class heavily based on discussion in which about 15 students were enrolled. Thanks to the diverse issues that they discussed in class, the course attracted students of many different races.

“It served a purpose for the students and the university because they got a chance to understand the large segment of unknown history,” Lou said.

The momentum for the strike built up after Lin and other leaders of AAAB attended the annual Asian American Conference held in Evanston. Lin said she was upset that Northwestern did not have a program that existed in many other institutions, especially in the West Coast. As AAAB wrote the proposal for a new Asian American Studies program, some of its leaders prepared for the protest, anticipating rejection from the university.

Their proposal was simple: hire one tenure-track professor for the ’95-’96 academic year and eventually create a program with at least three professors with tenure. It included the signatures of more than 1,200 students and letters of faculties who supported the program. However, what the administration offered—temporary programs taught by visiting lecturers—was far from a sustainable program.

“We submitted the proposal to let the administration know that this can be an academically viable program, not just a mental health support group,” Lin said.

Lin said that she was most frustrated at the lack of public knowledge about Asian America. It was a challenge for her to convince others that Asian American Studies is about America, not Asian countries, and is therefore a different program from Asian Studies. Nonetheless, AAAB gathered support from different student groups such as Latino and African American student groups as well as the LGBT student group. By forming an alliance with other minority groups, AAAB demonstrated that it was not only a few Asian students who wanted the program.

In the end, more than 60 students participated in the serial hunger strike that continued in the form of relay.

“This was before the Internet, social media and even email,” Lou said. “Organizing people required real conversations, persuasion and sometimes uncomfortable arguments.”

After gaining momentum, the protest started to receive national attention. Two weeks after the first day of the hunger strike, students at Columbia University, Stanford University and Princeton University demonstrated their support through sit-ins and fasting. The Chicago Tribune and local TV channels also covered AAAB’s protest.

However, not everyone in Northwestern supported the protest. A conservative student group ridiculed those who participated in the hunger strike by delivering pizza to the Rock and eating it in front of the strikers.

Although the African American Studies majors and the department faculties supported the strike, they had mixed feelings toward the new ethnic study program. Lin said because the university always gives only a small amount of resources to ethnic studies, they worried that a new program could take away their share of the tiny pie.

There were also conflicts within AAAB. Other leaders in the Board who did not lead the protest but who were in charge of other issues felt that the protest encroached on their space inside the group.

“It reflected how young we were,” Lou said. “But it’s also true that a lot of people who worked behind the scenes didn’t get enough recognition that me or Lin received.”

Lou emphasized that there are other people who deserve recognition, such as students who pushed for the program before them.

“We were just piggybacking off the momentum started by the people before us,” Lou said. “Likewise, after I stepped down, it was the people after us that carried the torch.”

People after her did carry the torch. Although the hunger strike was necessary to show the university how much the students wanted the program, the program was mostly shaped and designed by conversations between the student-led committee and the administration. After a long tug-of-war of negotiations, Asian American Studies was finally created as a minor program in 1999.

Since then, Asian American Studies has grown into a program that offers more than 20 courses taught by four core faculty members, a director and several lecturers. To this day, active student participation remains integral to the program. It was the students who organized Asian American Studies Strikes Back, which celebrated the 20th anniversary of the hunger strike.

Jinah Kim, assistant director of the Asian American Studies program, said that the program would die out unless the movement continues. Maintaining the energy and enthusiasm that created the program is a challenging task for all members of the Asian American Studies community.

Kim also said that the program is the study of the interaction between different peoples. The program provides students the chances to ponder the dynamics between different identities such as gender, race and socioeconomic status, and how these power relations work for or against them. Because Asian American culture includes many different people with dissimilar languages and customs, a state of solidarity is an incomplete project that its members continue to work towards.

“The power to be able to tell stories about ourselves in the ways that we want to tell others empowers us when entering the world,” Kim said.

However, Kim emphasized that the goal of the program is not to make people comfortable to talk about sensitive issues such as race and class. While talks on race and class are inherently uncomfortable, Kim believes that we have to bring about and be engaged in those conversations.

“One of the things that we all try to do in Asian American Studies is to encourage and develop routes for our students to connect what they learn in the classroom to things that are happening outside of them,” Kim said. “We are teaching them to become leaders of thinking and talking about race outside of the classroom.”

Weinberg junior Kevin Luong is an Asian American studies minor majoring in political science. According to Luong, the classes taught him that he could practice a significant amount of activism through academia: by teaching and learning the ideas and histories that are often forgotten, the faculty and students are not only changing the discourse inside the academia but also impacting society.

Luong said that Professor Kim convinced him to minor in the program. He was attracted to both the small but vibrant community that enabled profound discussions as well as the close attention he could receive from faculty members.

“One-to-one attention is something that you rarely get at Northwestern unless you actively seek it out,” Luong said. “Professors in this department will try to talk to you personally without you putting the first step forward, which is inviting and beneficial to underclassmen who are not acclimated to the college atmosphere.”

The struggle of the Asian American Studies community is not over. In an interview with The Daily Northwestern, history professor Ji-Yeon Yuh, the first hire for the Asian American Studies Program in 1999, said that faculty would submit a proposal to create an Asian American Studies major before the end of 2015. Kim said another struggle comes from claiming and maintaining the program’s own color and space inside the university. Ethnic minorities, Kim said, should refuse to participate in “the university’s story of diversity … (as) happy minorities.”

“As a Midwestern school, we are very privileged to have what we have here in Northwestern,” Luong said. “But that doesn’t mean there is no more work to be done.”

_________________________________________________________________________________

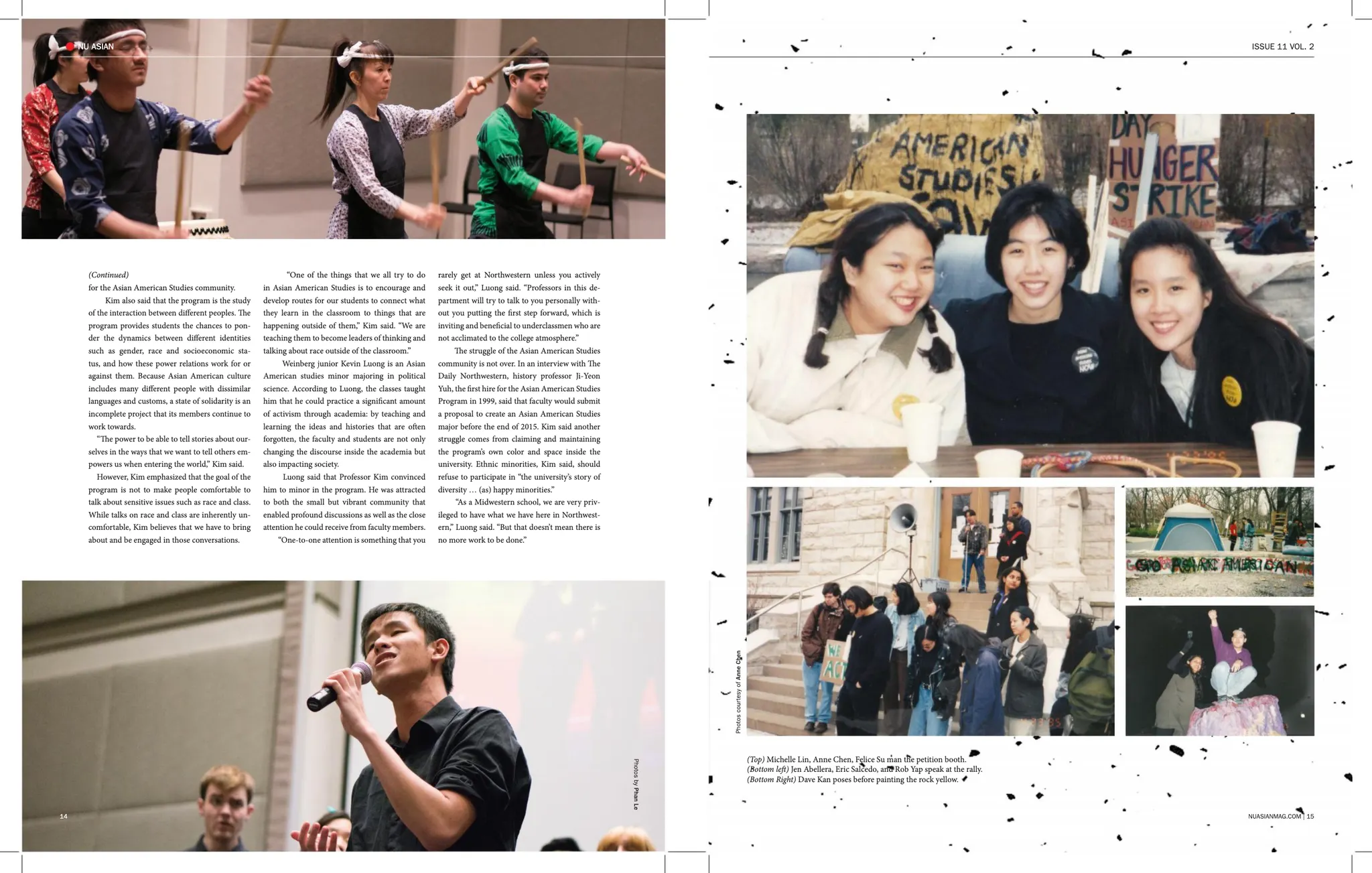

Rallies, chants, speeches, heated debates, sit-ins, and a hunger strike continued for 23 days.

In April 1995, Freda Lin was at the center of the protest as the vice chair of the Asian American Advisory Board, the student-led organization that started the protest. On the first day of the strike, with a megaphone in her hand, she led the crowd chanting “no program, no peace” from the Rock to the Rebecca Crown Center. The protesters occupied the administrative building and demanded formal conversation with Henry Bienen, former President of Northwestern University.

Northwestern’s Asian American Studies program was not a natural product of the university itself, but rather stemmed from a group of students who decided to protest against an administration that was apathetic to establishing a new ethnic studies program specific to Asian Americans. This year marks the 20th anniversary of the hunger strike that paved the way for the creation of the program in 1999.

Grace Lou, then President of AAAB, said she first saw the potential of the program as she led a student-organized seminar on the history and politics of Asian America. It was a small class heavily based on discussion in which about 15 students were enrolled. Thanks to the diverse issues that they discussed in class, the course attracted many other students of different races.

“It served a purpose for the students and the university too because they got a chance to understand the large segment of unknown history,” Lou said.

The momentum for the strike built up after Lin and other leaders of AAAB attended the annual Asian American Conference held in Evanston. Lin said she was upset that Northwestern did not have a program that existed in many other institutions, especially in the West Coast. As AAAB wrote the proposal for a new Asian American Studies program, some of its leaders prepared for the protest, anticipating rejection from the university.

Their proposal was simple: hire one tenure-track professor for the ’95-’96 academic year and eventually create a program with at least three professors with tenure. It included the signatures of more than 1,200 students and letters of faculties who supported the program. However, what the administration offered—temporary programs taught by visiting lecturers—was far from a sustainable program.

“We submitted the proposal to let the administration know that this can be an academically viable program, not just a mental heath support group,” said Lin.

Lin said she was most frustrated that people often did not understand what Asian America was about. It was a challenge for her to convince others that Asian American Studies is about America, not Asian countries, and is therefore a different program from Asian Studies. Nonetheless, AAAB gathered support from different student groups such as Latino and African American student groups and even the LGBT student group. By forming an alliance with other minority groups, AAAB demonstrated that it is not only a few Asian students who want the program.

“We wanted to be strategic about how it started,” Lou said. “The support of other organizations lent legitimacy to what we were doing.”

Lou said the active support for the protest impressed her because of Northwestern’s “sleepy” atmosphere. Because of the busy quarter system and the clear divide between north and south campuses, AAAB did not expect enthusiastic support from the student body. In the end, more than 60 students participated in the serial hunger strike that continued in a form of relay.

“This was before the Internet, social media and even email,” Lou said. “Organizing people required real conservations, persuasion and sometimes uncomfortable arguments.”

After gaining the momentum, the protest started to receive a national attention. Two weeks after the first day of the hunger strike, students in Columbia, Stanford and Princeton demonstrated their support through sit-ins and a fast. The Chicago Tribune and local TV channels also covered AAAB’s protest.

However, not everyone in Northwestern supported the protest. A conservative student group ridiculed those who participated in the hunger strike by delivering pizza to the Rock and eating it in front of the strikers.

Although the African American Studies majors and the department faculties supported the strike, they had mixed feelings toward the new ethnic study program. Lin said because the university always gives only a small amount of resources to ethnic studies, they worried that a new program could take away their share of the tiny pie.

There were also conflicts within AAAB. Other leaders in the Board who did not lead the protest but who were in charge of other issues felt that the protest encroached on their space inside the group.

“It reflected how young we were,” Lou said. “But it’s also true that a lot of people who worked behind the scenes didn’t get enough recognition that me or Lin received.”

Lou emphasized that there are other people who deserve recognition, such as students who pushed for the program before them.

“We were just piggybacking off the momentum started by the people before us,” Lou said. “Likewise, after I stepped down, it was the people after us that carried the torch.”

People after her did carry the torch. Although the hunger strike was necessary to show the university how much the students wanted the program, the program was mostly shaped and designed by conversations between the student-led committee and the administration. After a long tug-of-war of negotiations, Asian American Studies was finally created as a minor program in 1999.

Since then, Asian American Studies has grown into a program that offers more than 20 courses taught by four core faculty members, a director and several lecturers. To this day, active student participation remains integral to the program. It was the students who organized Asian American Studies Strikes Back, which celebrated the 20th anniversary of the hunger strike.

Jinah Kim, assistant director of the Asian American Studies program, said that the program would die out unless the movement continues. Maintaining the energy and enthusiasm that created the program is a challenging task for all members of the Asian American Studies community.

Kim also said that the program is the study of the interaction between different peoples. The program provides students the chances to ponder the dynamics between different identities such as gender, race and socioeconomic status, and how these power relations work for or against them. Because Asian American culture includes many different people with dissimilar languages and customs, a state of solidarity is an incomplete project that its members continue to work towards.

“The power to be able to tell stories about ourselves in the ways that we want to tell others empowers us when entering the world,” Kim said.

However, Kim emphasized that the goal of the program is not to make people comfortable to talk about sensitive issues such as race and class. While talks on race and class are inherently uncomfortable, Kim believes that we have to bring about and be engaged in those conversations.

“One of the things that we all try to do in Asian American Studies is to encourage and develop routes for our students to connect what they learn in the classroom to things that are happening outside of them,” Kim said. “We are teaching them to become leaders of thinking and talking about race outside of the classroom.”

Weinberg junior Kevin Luong is an Asian American studies minor majoring in political science. According to Luong, the classes taught him that he could practice a significant amount of activism through academia: by teaching and learning the ideas and histories that are often forgotten, the faculty and students are not only changing the discourse inside the academia but also impacting society.

Luong said that Professor Kim convinced him to minor in the program. He was attracted to both the small but vibrant community that enabled profound discussions as well as the close attention he could receive from faculty members.

“One-to-one attention is something that you rarely get at Northwestern unless you actively seek it out,” Luong said. “Professors in this department will try to talk to you personally without you putting the first step forward, which is inviting and beneficial to underclassmen who are not acclimated to the college atmosphere.”

The struggle of the Asian American Studies community is not over. In an interview with The Daily Northwestern, history professor Ji-Yeon Yuh, the first hire for the Asian American Studies Program in 1999, said that faculty would submit a proposal to create an Asian American Studies major before the end of 2015. Kim said another struggle comes from claiming and maintaining the program’s own color and space inside the university. Ethnic minorities, Kim said, should refuse to participate in “the university’s story of diversity … (as) happy minorities.”

“As a Midwestern school, we are very privileged to have what we have here in Northwestern,” Luong said. “But that doesn’t mean there is no more work to be done.”